Last week the Prague Security Studies Institute organized International Conference titled “NATO Strategic Concept: Response to Our Concerns?”. This piece is a first out of two reflecting some aspects of the conference.

Symbol of NATO, Brussels; Photo by NATO

The discussions about the new NATO strategic concept has reminded me summit of the NATO summit in Washington in 1999. The “war” summit was supposed to start the change of the alliance. In the following years the transformation should have taken place and even the crucial “identity” questions such “who are we”, “where are we heading to” etc. should have been addressed. Despite all of that a searching for the answers have been overshadowed by the self-interested dealing with internal rifts, and uncertainities about the sense of the alliance

Of course, the alliance has changed but, frankly, we have not moved as far as the member countries promised themselves on the summits in 1999 and 2002. When one of the speakers on the conference enumerated the successes of the alliance in the past 20 years, I could, rather bitterly and maybe unfairly, think only of one success: the alliance has somehow survived the end of the Cold War and the next two decades.

The introductory lines touch upon two major areas that have been discussed on the conference; the future of NATO connected with its reform that should be guarder by the new strategic concept (1), and the relations to Russia (2).

1) One of the speakers mentioned the motto of the 1990s: alliance must go out of the area or out of the business. Now it is time, he continued, for NATO to return into “the area”. While the alliance have focused on tackling the problems in the “outer area”, the credibility regarding its core task – defending the member countries – was severely hit by the events in Georgia in summer 2008.

I am not saying that the alliance would not be willing or able to defend its members. Rather, I would maintain that at least some members have lost the faith in it. We should still bear in mind that what matters is not what is true but what people think is a truth. The cases of Georgia crisis and looming problems in Afghanistan show that the alliance has not been missing will or means but rather trust and credibility. Some new members for example bitterly complain that NATO does not have the contingency plans which would “cover” the eastern part of the NATO’s territory.

2) The previous issue is connected with one of the main concerns of the conference – Russia. The impression is quite clear. No matter what we think about Russia in terms of considering her as a threat or in terms of dealing with her, she appears to be an omnipotent topic (not omnipotent power). Put it differently, whatever is the issue at stake, the debate ends with Russia; What would Russians think? What are they going to do?

This is exactly the case of putting the article 5 into doubts. What is behind the endeavours of some members to achieve new assurances about article 5? Are they afraid of Taliban, instability in Afghanistan, China or somebody else? No, it is all because of Russia.

Whereas the main threats officially emanate e.g. from Afghanistan (success or failure = existence or not existence of NATO), terrorism, failed states, rogues states with the WMDs, or from cyberspace, most of the Eastern countries see it differently. As oppose to the views of the main Western political representatives, the main threat to them has traditionally come from Russia. This issue has been causing tensions in NATO as well as in the EU.

The debate about Russia often slides to the problem of engagement. The conference included both harsh critics of Russia, who were sceptical about any possible relevant cooperation, as well as adherents of the closer and deeper engagement.

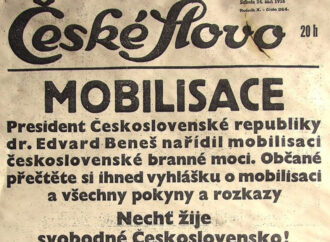

The engagement as such is an excellent idea. However, the problem is that the Russians accepts engagement only if they exercise a full control over the process. Read for example Russian advice on Afghanistan written by Boris Gromov and Dmitry Rogozin (Russian ambassador to NATO). They argue that Russia (USSR) was first defending the Western civilization against the Muslim fanatics and while the West is doing even worse mistakes, Russia is still willing to help. (Reading between the lines: like older and smarter brothers always do). If NATO will be willing to approach Russia as a more experienced brother, the engagement will work. Is it worth accepting? Russia will take part of the game only in case she is considered as the smartest and mightiest in the class. At the same time, she will shape the reality, rules, and, indeed, history according to her liking.

After all, the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1989 was not a shameful escape accompanied by the mujahadeen’s celebrations. The Soviet Army entered the country, accomplished its tasks — unlike the Americans in Vietnam — and returned to its motherland.

Indeed, Russia plays a bigger role in the discussions than it should play. The reason is obsession of Eastern member states of NATO by her. While it is to a certain extend understandable, majority of the old member states do not comprehend this and consider this obsession as exaggerated. I do not want to overdo this “cleavage” but the distrust within the alliance is much more dangerous then the potential failure in Afghanistan.

Several steps might easily improve the internal situation without necessarily complicating the relations with Russia. NATO could, for example, increase the number of instalments in the new member countries, organize exercises within the current NATO borders, and prepare contingency plans while keeping transparent and opened communication channels with Russia. The point is that the alliance must not play the game according to the Russian’s rules.

The alliances do not need their enemies. They exist until they serve the interests of their members. What are these interests nowadays and how NATO can address them? These two questions should be clearly answered in the new strategic concept. Trying to satisfy everyone in the new strategy would be a mistake. Alliance is not and cannot be the right tool for everything, nor it is the only tool. We should not seek maximum, we should seek the least common denominator. Since the very beginning of NATO it has been the territorial defence of members. Let us return and start out strategy from there.

2 comments

2 Comments

Tomáš Karásek

21. 1. 2010, 17:19Nice outline, but I guess there are good reasons not to be as gloomy as the author suggests:

Concerning the situation on Georgia, we can argue whether the Western stance should have been firmer – I certainly think it wouldn’t have hurt. But let’s not forget that Georgia is not a part of NATO’s collective defence obligation. To interpret NATO’s inaction in her case as a proof a weakening commitment to the defence of its members is simply too farfetched.

Secondly, though the suspicion of Russia among the „new“ member states is understandable and to much extent justified, it would be a grave mistake to try to make NATO revolve around it, given the array of global challanges which Europe and the U.S. are and will be facing. Russia is a state that – apart from its nuclear arsenal and oversized military (but do we really think Russia would start a military conflict with NATO?) – is clearly boxing above its weight. In not so far a future, its population will drop to the level of Turkey. Due to the ineptitude of Russian political elites to wean its economy away from the dependency on the export of natural resources, the same will become true of its economy.

Does it mean Russia’s not dangerous? Of course not, but its capabilities simply fade in comparison with the aggregate NATO power (both political and economic, not to speak about soft power). Simply put, Russia’s no match for NATO if the Alliance is able to maintain its unity. Once the NATO realizes this, it should be much easier to avoid the usual hystery and implement practical policies which counter the partial but real threats which Russia poses for some of the member states in Eastern Europe. To end with a paraphrase from FDR, I really believe that in the case of Russia the only thing that NATO should fear is fear itself.

REPLY