Organizace Open Society Justice Initiative vydala včera zprávu s názvem Globalizing Torture: CIA Secret Detention and Extraordinary Rendition, ve které shrnuje informace, z otevřených a dalších zdrojů, k zadržování teroristů, jejich převážení po světě a mučení Ústřední zpravodajskou službou (CIA). Je rozdělená na několik částí věnujících se právnímu i politickému pozadí převážení lidí do jiných zemí k výslechům, mučení, seznamu 136 teroristů, kteří se po 11. září ocitli v rukách CIA a seznamu zemí, které CIA napomáhaly.

Česká republika je mezi 54 zeměmi uvedena. Nic nového v textu vážícího se k ČR ovšem není:

The Czech Republic allowed the use of its airports and airspace for flights associated with CIA extraordinary rendition operations. The U.N. Human Rights Committee and other organizations have alleged that rendition flights included layovers in Czech airports on the way to countries where detainees were at risk of torture or ill-treatment. The Human Rights Committee requested an investigation of rendition through Czech airports, but the Czech government denied any knowledge of such incidents.

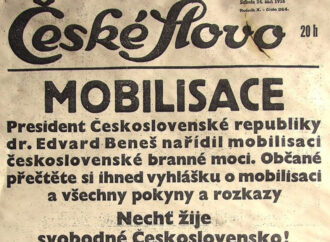

V seznamu jsou uvedeny státy, které byly mnohem aktivnější a pomáhaly v rámci „války proti terorismu“, která – soudě podle reakcí a médií – měla po útocích z 11. září 2001 v euroatlantickém prostoru snad devadesáti procentní podporu. Praxe po 11. září je zajímavým předmětem ke studiu z hlediska právního, filosofického, politického i bezpečnostního. Pamatuji si na jeden komentář v roce 2001, ve kterém jsem se tázal, zda jsme připraveni na to, že v rámci boje proti terorismu, po kterém tehdy všichni volali, se budou odehrávat i nepěkné věci. Odpověď jsem dostal až po letech, připraveni jsme nebyli a asi nikdy nebudeme (šlo o dotaz vycházející z historické zkušenosti a z jednoduché úvahy – když pustím psy ze řetězu, tak je vyšší pravděpodobnost, že někoho pokoušou).

Bývalý ředitel CIA Michael Hyden minulý týden řekl:

We are often put in a situation where we are bitterly accused of not doing enough to defend America when people feel endangered. And then as soon as we’ve made people feel safe again, we’re accused of doing too much.

Z mučení se stalo velké téma a nejeden film a kniha se s ním vypořádává jako s něčím ďábelským, čímž jsme se zaprodali. Dospěli jsme do vývojového stádia, kdy jsme v našem prostoru odvrhli některé typy chování a trestů jako nežádoucí – trest smrti, mučení, rasismus a tak dále. Je nutné, pokud se objeví případy porušující tyto normy opakovat si, že je to špatné, ale není možné se domnívat, že zákazem vymizí. Jak napsal Steve Coll v New York Review of Books v recenzi na film Zero Dark Thirty:

Even if torture worked, it could never be justified because it is immoral. Yet state-sanctioned, formally organized forms of torture recur even in developed democracies because some public leaders have been willing to attach their prestige to an argument that in circumstances of national emergency, torture may be necessary because it will extract timely intelligence relevant to public safety when more humane methods of interrogation will not.

Chápu, že jsou normy, které se nemají překračovat, protože jsme si řekli, že je to nevhodné. Co ale nechápu, je zcela zbytečná hysterie kolem. A tak se třeba těším a zároveň se i bojím filmu Zero Dark Thirty (v češtině 30 minut po půlnoci), dalšího snímku s válečnou tématikou od režisérky Kathryn Bigelow. Pokud je tím hlavním, co zůstává v hlavách diváků (soudím tak po přečtení rozličných recenzí) po zhlédnutí filmu to, že bez mučení by CIA nedopadla Usámu bin Ládina, pak se není na co těšit (zároveň doufám, že tomu tak nebude). Film vyvolá debatu a pocity, které jsou, alespoň podle různých textů a knih popisujících hon na bin Ládina, mimo mísu. I bez mučení se CIA dostala na stopu vůdce Al Kajdy.

14 comments

14 Comments

Robert Keřlík

7. 2. 2013, 20:25Co se týče filmu, není se čeho bát. Jen celkem realisticky ukazuje fakt, že náboženský fanatik prostě neřekne cenné informace vyšetřovateli, jen proto aby dostal místo 50 let 20 let vězení a proto se musí používat i jiné metody výslechu. Ostatně i CIA přiznala, že hlavně na začátku války s terorismem jim takto získané informace pomohli zachránit spoustu lidských životů, když se jim díky tomu podařilo překazit některé akce teroristů. Film je hodně povedený a určitě není jen o mučení, ale o všem co předcházelo samotné DA na dopadení Bin Ládina a i na tu se ve filmu dá koukat :)

REPLYIvo

7. 2. 2013, 21:45Před několika týdny jsem absolvoval na škole velmi zajímavou diskusi na toto téma. Několik postřehů z ní:

1. Velká Británie byla při Bitvě o Británii a Bitvě o Atlantik v nepopsatelě větším nebezpečí a ztratila o několik řádů více vojáků i civilního obyvatelstva než dnes Američané při „Válce proti terorismu“. Přesto se Britové nikdy neuchýlili k mučení německých zajatců, i když obě dvě tyto „bitvy“ byly vyhrány z velké části díky zpravodajství. Přitom německých zajatců měli dostatek. Proč?

2. Představte si, že padne rozhodnutí těmto vyšetřovacím technikám dát úřední razítko? Kdo bude tyto specialisty cvičit a jak? Na základě jakých kritérií bude prováděn výběr? Jak se bude nové ČVO „Mučitel“ jmenovat a součástí jaké kariérní cesty bude?

3. Představte si, že je pořádán charitativní večírek, kam jsou pozváni jako čestní hosté zástupci ozbrojených složek. Po přípitku si tři zástupci ozbrojených sil sednou ke třem stolům a začne večeře, civilisté si mohou sednout dle své libovůle k oněm třem stolům. U večeře se očekává zdvořilá konverzace na téma těžké služby těchto vojáků. U dvou stolů je narváno, ke třetímu seí nikdo nechce sednout. Proč – ti vojáci byli výsadkář, tankista a zástupce „nového ČVO“…

4. Je třeba si přiznat, že určité věci jsou neslučitelné s naším způsobem života potažmo euroatlantickou civilizací tak jak ji známe. I když některé tyto techniky mohou být efektivní, tak v dlouhodobém horizontu jen vyšují počet teroristů. Všichni si stále pamatujeme na Abu Graib, a Guantanamo se marně pokouší zrušit už třetí administrativa USA…

REPLYŠťoural

7. 2. 2013, 21:58Obávám se,že se místnímu hospodáři během jeho mise v státním sektoru vychýlil morální kompas(sorry Franto).Největší problém mučení není to že je amorální.Problém je že nefunguje.Ať si DCI Hyden říká co chce LŽE!!!

Může me být jenom rádi že v té době jsme měli za premiera V.Špidlu.A to rozhodně nejsem jeho fanoušek.S Zemanem,Grossem,Topolánkem nebo Nečasem bychom v tom byli namočení jako poláci.

DOPORUČENÝ MATERIÁL PRO MLÁTIČKY

1)Úryvek z knihy The Longest War Peter Bergena

On August 1, 2002, the White House lawyer John Yoo wrote a classified memo narrowly defining the crime of torture. According to Yoo, American interrogators could legally inflict pain short of that “accompanying serious physical injury such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death.” Interrogators could also inflict mental pain, but only short of the point where it resulted “in significant psychological harm of significant duration, e.g., lasting for months or even years.” The memo also concluded that inflicting “cruel, inhuman, or degrading” treatment on a prisoner wasn’t necessarily something that American interrogators risked being prosecuted for. This seemed more the reasoning of a mob enforcer than an official in the Office of Legal Counsel, the White House’s elite group of in-house lawyers, whose opinions guide the actions of the executive branch. (And if these were the opinions of a Harvard-educated, Supreme Court clerk turned law professor, as Yoo was, it is not entirely surprising that, as these ideas filtered down to soldiers in the rank and file, you ended up with the human pyramids of naked Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib.)

Zein al-Abideen Mohamed Hussein, generally known as Abu Zubaydah, a Palestinian al-Qaeda logistician in his early thirties, was believed to be the highest-ranking member of the terror group to be taken alive in the first months after 9/11. That made him the subject of intense interest from American officials, since, by early 2002, there was no one as yet in custody who they believed could tell them about what form the next terror attack might take. As a result, many of the Bush administration’s coercive interrogation techniques would first be applied to Abu Zubaydah.

In February 2002, the CIA station in Islamabad had learned that Abu Zubaydah was either in Lahore or Faisalabad, Pakistani cities with large populations in the east of the country. Intelligence officials also discovered Abu Zubaydah’s cell phone number, but he used it only briefly and infrequently. Agency officials narrowed down to fourteen the possible locations where Abu Zubaydah might be living. At 2 A.M. on March 28, 2002, Pakistani army units hit all of them.

Abu Zubaydah was captured in a shoot-out in Faisalabad in which he was shot three times and critically wounded, losing a testicle in the firefight. So grave was Abu Zubaydah’s condition that the CIA arranged for a leading surgeon from the Johns Hopkins Medical Center in Baltimore to fly to Pakistan to save his life and revive him to the point that he could be interrogated.

The interrogation of Abu Zubaydah set the stage for a carefully concealed battle between the FBI and elements of the CIA, backed by senior Bush administration officials, about how best to obtain information from suspected terrorists in American custody. The Bureau favored traditional rapport-building techniques, while some Agency and White House officials successfully pushed for coercive interrogations that verged on torture.

Abu Zubaydah was the first detainee to be placed in a secret overseas CIA prison, this one located in Thailand. There he was interrogated by Ali Soufan, one of the few Arabic-speaking FBI agents. Soufan softened up Abu Zubaydah by calling him “Hani,” the childhood nickname his mother had used for him, a fact that the FBI agent had gathered from intelligence files. The approach started yielding quick results.

When Abu Zubaydah was shown a series of photos of al-Qaeda members by Soufan, he identified Khalid Sheikh Mohammed as “Mukhtar,” meaning “the chosen” in Arabic. This was a key to unraveling one of the great mysteries of the attacks on New York and Washington, because in an al-Qaeda videotape recovered by American forces in Afghanistan a few months after 9/11, bin Laden had referred to a “Mukhtar” as someone who had some sort of a plan for a “tall building in America.”

Soufan remembers puzzling over the bin Laden videotape. “It was annoying the shit out of me: Who is Mukhtar?” Abu Zubaydah had now identified Mukhtar to be Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. KSM had been known as a jihadist to U.S. authorities since 1993, when his name surfaced in the FBI’s investigation of the World Trade Center bombing; but his central role in 9/11 came as a complete surprise to investigators.

Abu Zubaydah’s confirmation of KSM’s role in 9/11 was the single most important piece of information uncovered about al-Qaeda after the attacks on the Trade Center and Pentagon, and it was discovered during the course of a standard interrogation, without recourse to any form of coercion. Soufan recalled that Abu Zubaydah gave up the information about a week or so into his interrogation.

In the top-secret memoranda prepared by the White House’s Office of Legal Counsel that authorized coercive interrogation techniques on Abu Zubaydah, he was variously described as “one of the highest ranking members of al-Qaeda,” either the number three or four in the terror group, and as one of the planners of 9/11. In fact, within weeks of Abu Zubaydah’s capture it became clear to at least some U.S. officials that he was not “al-Qaeda’s chief of operations,” as he had been publicly described by President Bush on June 6, 2002, but rather someone who was a logistician for militants in Pakistan on their way to training camps in Afghanistan. Daniel Coleman, the al-Qaeda expert at the FBI, says that Abu Zubaydah was simply a “travel agent; he wasn’t a member of the inner circle” who would know about future operations, although he did know many members of al-Qaeda by virtue of his role as a “safe house keeper.”

But believing that Abu Zubaydah was, in fact, a very big al-Qaeda fish, the White House lawyers authorized continuous sleep deprivation of up to 180 hours (one week), face slapping, extended nudity (including in front of females), dietary manipulation, confinement in cramped boxes, being slammed into a flexible wall and, of course, “the waterboard.” The Office of Legal Counsel noted that these techniques were supposed to induce “a state of learned helplessness” in the detainee, who would then supposedly be putty in his interrogator’s hands.

This piece of pseudoscience was the brainchild of James E. Mitchell, a retired psychologist who had worked with the military’s SERE program (Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape), which is used to train American soldiers how to resist coercive interrogations, in the event that they are captured. In late 2001, Mitchell had coauthored a classified paper, “Recognizing and Developing Countermeasures to Al-Qaida Resistance to Interrogation Techniques.” Mitchell had never conducted a real interrogation and so had no sense of what worked in the real world to elicit information from prisoners, but that did not stop him from helping to develop aggressive “Enhanced Interrogation Techniques” to be used on al-Qaeda detainees. Those techniques included confinement in a small box, stress positions, sleep deprivation for days, and waterboarding; one or more of these were later used on a total of twenty-eight detainees in American custody.

In mid-April, around ten days after Soufan had first started interrogating Abu Zubaydah, and over the FBI agent’s vociferous objections, a CIA contractor stepped in to take over the interrogation. The FBI’s standard, noncoercive techniques were jettisoned and Abu Zubaydah was stripped naked, deprived of sleep, subjected to loud noise and wide variations in temperature, and isolated from Soufan and other professional interrogators. The CIA contractor would now appoint Abu Zubaydah’s “God,” who would exercise total control over him. Soufan recalls: “Only one person and one person only from now on would have access to Abu Zubaydah. … The interrogation style was to go in and tell him, ‘Tell me what I need to know.’”

The CIA contractor, a psychologist, had not interrogated anyone before, nor did he know anything about Islamist extremists or the Middle East. Soufan and the other professional interrogators with him watched the new approach unfold with astonishment. Soufan says that at one point Abu Zubaydah was sitting naked on the floor, and the CIA contractor insisted that his new experimental interrogation techniques were working on the prisoner: “He’s like, ‘See! See! He tilted his head to the right: That means it’s working. He’s contemplating, he’s thinking, because he tilted his head to the right—he’s in agreement, he’s going with the program.’ … The contractor gets so excited he had a fucking boner.’” Abu Zubaydah then promptly fell asleep, snoring loudly.

Soufan objected to the CIA that Zubaydah was being subjected to “borderline torture,” and “other people who were on the ground were going on the computers and shooting cables back to Washington” to complain about the new interrogation regime. By now Abu Zubaydah was no longer giving up any significant information.

Eventually, Soufan and the other professional interrogators were allowed to resume their questioning of Zubaydah. It was then that he described an Hispanic al-Qaeda wannabe whose physical description jibed with that of Jose Padilla, an American small-time hood who would later be arrested at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport in May 2002, supposedly planning to detonate a radiological “dirty bomb” in the United States.

Scott Shumate, a psychologist working with the CIA who was present during Abu Zubaydah’s interrogations, was so disgusted by the interrogation regime instituted by the Agency contractor that he flew home. On May 25, almost two months after he had first started interrogating Abu Zubaydah, so too did Ali Soufan, pulled out on the orders of his FBI superiors, who did not want the Bureau’s agents to be involved in coercive interrogations.

Abu Zubaydah was later “waterboarded” eighty-three times by the CIA. This form of simulated drowning is generally considered torture, but none of it produced much in the way of useful information. General Michael Hayden, who served as CIA director in the last two years of the Bush administration, claimed that waterboarding Abu Zubaydah did yield key information that led to the capture of Ramzi Binalshibh, who had helped to oversee the 9/11 plot. But there may be a problem with Hayden’s chronology because water-boarding wasn’t authorized until August 1, 2002, four months after Zubaydah was arrested, and Binalshibh’s name was by then already well-known to the U.S. government and indeed to the world, as he was the subject of a front-page story in the New York Times ten weeks before he was captured, on September 11, 2002.

In the end the multiple waterboardings of Abu Zubaydah provided no specific leads on any plots, although clearly his role as an al-Qaeda logistician did give him insights into the organization and its personnel. Dozens of videotapes of the CIA interrogations of Abu Zubaydah were destroyed in 2005 by a senior CIA official, Jose Rodriguez, who seems to have calculated that if the tapes ever entered the public domain they would have caused the same kind of outrage that greeted the Abu Ghraib prison abuse photographs from Iraq. It is one thing to read about abuses; it is quite another to watch them unfold in front of your eyes.

2)O výslechových metodách The Dark Art of Interrogation,Mark Bowden

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2003/10/the-dark-art-of-interrogation/302791/

REPLYFrantišek Šulc

7. 2. 2013, 23:45Honzo, popravdě, moc mučení jsem ve státní správě neprovedl (kromě několika přednášení myšlenek, což může být mučením, uznávám), takže jestli funguje, nefunguje, nemám tušení. Nevím, kolik mučeníček máš za sebou Ty. V článcích a knihách je toho hodně, ale mimo ně také dost…

Ale vážně, nemohl se mi vychýlit morální kompas, pokud jsem toho názoru, že je mučení amorální. To nařčení nedává smysl. A navíc, to, že něco nefunguje není v rozporu s tím, jestli je to morální, nebo amorální. Takže v Tvém tvrzení není příliš logiky. Vzhledem k tomu, že debata o tom, jestli mučení funguje, nebo nefunguje nikam nevede a nepovede, pak je lepší přistoupit na to, že nepatří do našeho hodnotového světa, čímž řeknu ne, aniž bych musel dokazovat, kdo má pravdu (což je ztráta času). Hezky to vystihuje citát z Collovy recenze.

REPLYRobert Keřlík

8. 2. 2013, 0:29To Ivo: Nelze nesouhlasit s tím, že mučení nepatří do moderních ozbrojených složek a zpravodajských služeb. Nicméně si myslím že i když někdo tvrdí že zajatce nemučí, nemusí to být 100% pravda, to k těm Britům. Taky jim trvalo než se přiznali že dělali pokusy na lidech s chemickými zbraněmi i když to byli „dobrovolníci“. To že si někteří příslušníci US Army natáčeli a fotili vězně v průběhu týrání a mučení a pak se s tím chlubili veřejně jen způsobilo, že se o mučení dozvěděl celý svět a následně se s různými svědectvími o mučení doslova roztrhl pytel. Ale můžeme se někdy dozvědět pravdu o způsobech výslechu zadržených teroristů agenty zpravodajských služeb? Myslím si že ne. To je prostě jejich pískoviště a pokud jejich nadřízení budou dostávat cenné informace, tak k nim na to pískoviště nikoho nepustí a bude jim jedno jestli vězeň byl vystaven spánkové deprivaci nebo waterboardingu nebo halucinogenům atp. To ostatně potvrdil i bývalý viceprezident USA D. Cheney, který o waterboardingu prohlásil že je cenným zdrojem informací. Mimochodem Amnesty Int. stále ještě nepovažuje waterboarding za mučení protože to není právně podložené. I u nás probíhalo mučení a není to zas tak dávno. Političtí vězni by mohli vyprávět o životě za mřížemi. Kolik těchto případů se opravdu vyřešilo za těch uplynulých 23 let? A myslet si že mučení zmizí vydáním zákazu je naivní představa. Ostatně i proto se příslušníci speciálních sil na celém světě učí jak zvládnout mučení a rozpoznat moment kdy můžou začít uvolňovat určité informace aby nedošlo k ohrožení těch co unikli zajetí a probíhající operace a sami nebyli nějak ohroženi na životě právě mučením. Jinak je zajímavé že právě poznatky o tom jak nejlépe mučit bez tělesné újmy pochází často od těch co mají naopak pomáhat lidem – od lékařů, od těch co složili Hippokratovu přísahu.

REPLY