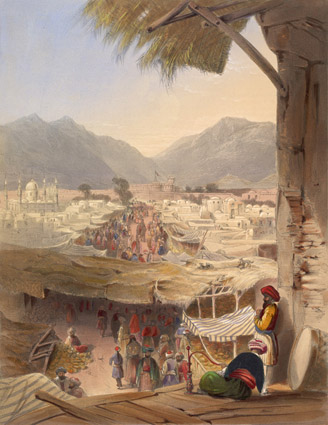

Kandahár v polovině 19. století, kolorovaná litografie, autor: Robert C. Carrick; Zdroj British Library (online gallery)

Mám rád jejich stránky a, proč to nepřiznat, obdivuji je. Rád sleduji jejich web a čekám, co tam přibude nového. Je fakt, že blog nyní trochu stagnuje, ale o to s větší chutí jsem si přečetl jejich článek v listopadovém/prosincovém vydání Foreign Policy „See you soon, if we´re still alive„. A těším se na knihu, která má vyjít příští rok.

Alex Strick van Linschoten a Felix Kuehn jsou dva mladí Evropané, kteří už rok a půl žijí v afghánském Kandaháru. Uprostřed města a bez bodyguardů. Přežili mnohé a dokázali se vylhat z řady nepříjemných situací. Jejich postřehy jsou skvělé a mohou sloužit jako lakmusový papírek toho, co se děje a zároveň jako „převodová skříň“ mezi námi etnocentickými Evropany (jen si to připustme) a hrdým paštunským jihem.

Zaujaly mně tři pasáže v jejich článku. První popisuje Taliban:

The Taliban are a mixed bunch of characters, and most Afghans here have some link to them. Everyday fighters are drawn from the huge numbers of unemployed, uneducated young men who dominate the rural population, and commanders often are the same figures who fought against the Soviets in the 1980s. Some join the Taliban because they lack a better occupation or a forward-looking vision in their lives; others, out of revenge, religious nationalism, or the simple wish to be left alone. But whatever the motivation, their reasons should be heard.

Druhá se týká paštunské kultury a Talibanu:

Perhaps most notably, we’ve seen that the Pashtun tribal system, still damaged from years of war and foreign interference, is again becoming the first point of call to settle disputes between locals and others — be they the government or the Taliban. Honor is the cornerstone of Pashtunwali, the famed tribal code meant to govern all Pashtun conduct from land disputes to revenge, but so, it seems, is survival.

We’ve also learned that the Taliban transcend Pashtun culture, though they came from the midst of it; their ideology and goals are not formed by their tribal or ethnic identity. And we have worked hard to start to understand how the Taliban have shaped Kandahar’s recent history, conducting dozens of interviews with Afghans who played key roles in the conflicts of the past 30 years and working with Mullah Zaeef to edit and explain his life story.

Indeed, Mullah Zaeef’s life offers many examples of the searing effects of decades of war. At 15, he joined the jihad, leaving his family and the refugee camp back in Pakistan. In reality just a boy, he fought alongside many of those who would later become the founders of the Taliban. His life, since before he was born, has been inscribed with the lines of conflict and loss, betrayal and sacrifice. Today, he is unable to live in Kandahar on accounts of threats from all sides, and he spends much of his time in Kabul explaining and advocating the Taliban position.

A nakonec náznak toho, co může Západ čekat, pokud se bude soustředit pouze na města:

But no matter how bad or good things become in the city, in the end the war is being lost — and will be lost — in the villages, especially those of the four overwhelmingly rural provinces that make up Loy, or greater Kandahar. Attempts to „protect the people“ along belts of security in the cities are perhaps honorable by intention, but they will not end the conflict. Real security — whether behind blast walls in Kabul, inside armored vehicles, or beneath Kevlar flak jackets — remains an illusion. In Kandahar, the simple rule is that everything is ok until it is not.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *