The following text is a summary from author’s new book The European Union as Security Actor of a New Type.

In the contemporary, interdependent world, a power to influence global events has been “in many hands on many places.” The transformation of the global distribution of power brings important implications for security and defense policy. These implications are derived from the mutual interdependence of individual actors in crisis-solving, decision-making, trade, and accessibility of energy resources, forming an overriding “paradigm of the post-bipolar world …where everything depends on everything.” Cooperation in an ever-wider set of issues, including security, has become the motto of the day.

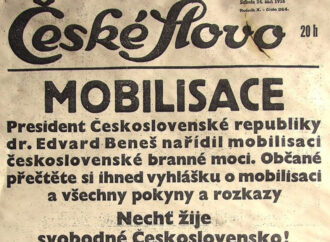

The post-Westphalian nature of international relations have thus driven the Atlantic Europe, Core Europe, New Europe, and Non-Aligned Europe to develop increasingly convergent strategic cultures based on mutually shared identities and interest in maintaining peace after centuries of horrible wars. Members of the community had gradually identified positively with one another, and security has become perceived as the responsibility of all as opposed to competitive or individualistic security systems of the Old Continent´s past.

Security Policy beyond Military Means

The European Union has succeeded in promoting peace internally, and ever-more actively tries to also export its experience behind borders. Today, the ever-close cooperation among states goes well beyond civilian aspects to include military and intelligence issues. Acting as a group, the EU uses its leverage through principles of conditional support to its neighborhood in order to promote peace and stability at its periphery and beyond.

Ability of the European Union to play such an important role in “alleviation of threats to cherished values,” is tightly connected with the existing identity (the manner of self-perception), which is closely tied to a strategic culture, and finally, it depends on its capacity to transform the theoretical prerequisites into real power to held responsible other actors, and to incur obligations.”

To act in such a manner, military means, scarcely at the EU´s disposal, are often not required. While military capacity remains an important factor in providing security, its role has changed. In today’s strategic environment, the military inevitably serves more as a support and a boost for different forms of security action – soft and normative power. The traditionally perceived “hard power” inevitably derived from largely inherited circumstances – geography, population, and raw materials. Yet eventually the concept of power gradually became ever more complex to include education, technology, economic growth, and cultural products, together forming a “soft power”. A high level of development in all these aspects is characteristic for all members of the EU, motivates them to maintain peaceful coexistence and gives them a considerable leverage when pressuring for its interests outside of its territory.

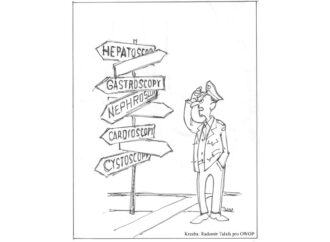

In accordance with the Clausewitzian dictum, the means changed as political objectives to be pursued with them had transformed. Emphasis has been put on building instead of destroying, stabilizing instead of conquering. Peace-building, conflict prevention, controlling migration, promoting good governance, tracking down terrorist groups, overseeing the movement of arms and preventing the spread of WMDs, reducing poverty, securing transit and communications routes, protecting electronic data, tackling environmental challenges, fighting infectious diseases, or promoting global economic sustainability are areas that go well beyond conventional means at an army´s disposal.

According to landmark essay Power and Interdependence by Joseph Nye and Robert Keohane, force, while necessary in extreme cases, has been generally losing its importance and is often not an appropriate way of achieving actor´s goals, peace and security being the most important among them.

A Framework to Build Upon

This is why a non-state entity with no common military force, but inevitably limited military cooperation, can aspire to be a force to be counted with in this intractable security environment. When danger of a conquering war between the EU states stepped aside to threats difficult to be dealt with individually, the peaceful coexistence within the borders of the Union has been further reinforced. This cohabitation is certainly based not only on values and ideas, but also on common interests. But even through a strictly realist view, omitting values as the driving force behind the ever-growing closeness of the EU Member States, the shared interests of these countries have produced tangible results in the field of security and defense policy. These are reflected in documents and concrete policy measures, agreed upon unanimously and lived up to by all member-states.

The scope of EU external activities within the CSDP is largely predetermined by two key documents, the European Security Strategy outlining threats, and the (extended) Petersberg Tasks, incorporated into the Treaty of Amsterdam signed in 1997 (effective in 1999). The Tasks include humanitarian and rescue missions as well as combat forces for crisis management and joint disarmament operations.

To be able to cover a relatively large scope of tasks assigned by the Petersberg Tasks and by the ESS, Helsinki Headline Goals 2010 acknowledges that the EU “must retain ability to conduct concurrent operations simultaneously.” To achieve that, individual national capacities must be increasingly interoperable, deployable in distant theatres, which can be, according to the document, best achieved by increased pooling and sharing. The Capability Development Mechanism should ensure that the capabilities are enhanced in coordination with NATO in order to fully exploit the potential of the Berlin Plus. Furthermore, the Member States have agreed to form EU Battlegroups (BGs), 1500-man-strong units capable of rapid response within 10 days after decision. Despite being operational since 2007, they yet have not been deployed. Nevertheless, the BGs concept has so far “substantially supported the transformation of the [national] armed forces and intensified national defence reform process.”

Thus, the formalized Common Security and Defence Policy with its wide range of instruments and a solid institutional base, have enabled the Union to play a role in security policy. The tide of globalization and EU internal development has swept the Union into becoming a security actor.

Through its various instruments, the EU aims to break a vicious cycle of weak governance and related phenomena by massive financial and technical support. The European Union is by far the world´s largest source of Official Development Aid (ODA), accounting for around 60% of the world total in 2010, at the height of the financial crisis. More than one third of a total of 53.5 billion € in 2010 went to direct conflict prevention, strengthening governance in fragile states, and governmental and institutional reform, and consequently the Palestinian Authority, Afghanistan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo were the biggest recipients. However the EU continuously fails to meet the target of giving 0.7% of GNP for ODA each year – in 2011 the member states donated 0.43% of GNP on average – but nonetheless the initiatives continue to play a significant role by indirectly countering some of the ESS threats in the area where they originate.

The EU deploys non-military means to tackle security concerns far from its borders also directly. Various preventive or post-conflict civilian missions, including police, lawyers, judges, civil administrators, customs officials, relief agents, and other specialists, often prove more effective in promoting stability than military power. The largest mission deployed so far has been EULEX, sent in 2008 to Kosovo. All of the more than 2,000 employees are non-military personnel.

Challenges Remain

However, as Nye and Keohane admit, even in the world of interdependence, there are limits on what can be achieved without being backed by credible military power. In line with Thomas Schelling´s observation, to be credible, one must appear to be able and willing to move further, without ever actually having to do so. In another words, to develop a truly sustainable, coherent global security presence, the EU must eventually overcome existing conceptual, organizational, and capability issues and possess credible and operable military capacities.

An easily attainable and flexible consensus on the use of military force thus remains the key challenge. An enhanced cooperation in the defense sphere, including defense industry and procurement as called for in the final document from the European Council meeting in December 2013, could be an important step in this direction. Also, finding an effective balance alongside NATO might further strengthen the EU´s efforts.

The European Union, a grouping of members that – despite their past of bloody wars against each other – have become unified by their common values and interests and finds itself at the forefront of the efforts to tackle most of the present security challenges. While far from being perfect, the EU´s activities in the promotion of democracy and stability, in fighting transnational organized crime, terrorism, cyber threats, or environmental risks have gone beyond its territory and resound also in the Union´s neighborhood. Through a number of programs and instruments, the EU aims to build on its developed common strategic culture and reflect the present international environment that makes cooperation to be a requirement in many cases. The Member states have often been working through the EU not for altruistic reasons, but because ensuring security at home, and having a stable and democratic neighborhood can be best achieved through the instrument that EU offers. The Union might more and more often serve as a new means towards transformed ends. Yet the underlying motivation of these ends remains unchanged: to ensure a state´s security.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *